Story by Ken Duke

If you missed Part 1 of this story, please go back and check it out. I’ll recap a little here, but you’ll have a better understanding of Florida’s world record smallmouths if you read the whole thing.

In a nutshell, Florida began stocking smallmouth bass more than a century ago, and giant “smallmouth bass” began popping up in lakes all over the Sunshine State … even lakes where they hadn’t been stocked!

The world record for smallmouths reached the teens in the 1930s and was at 14 pounds by 1932—in Florida! But pictures of those fish looked quite a bit like largemouths.

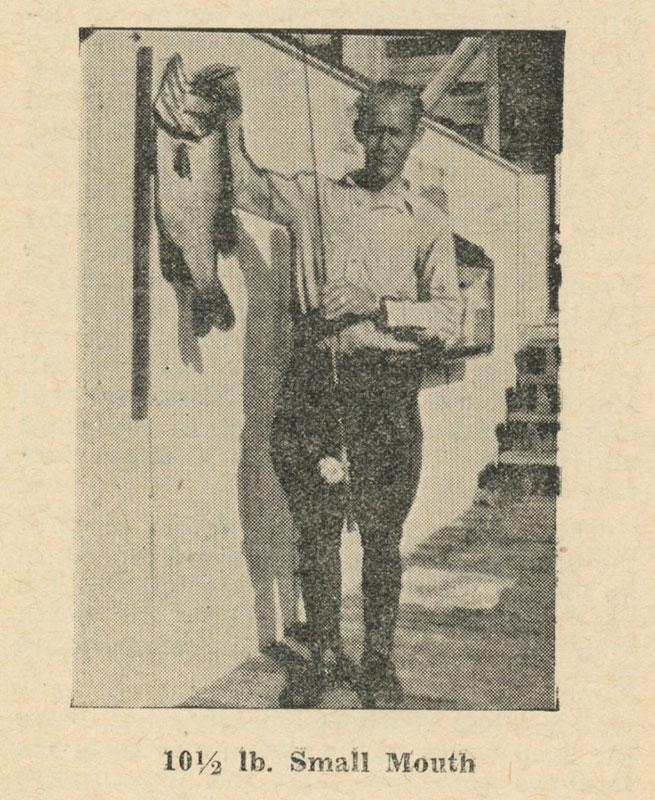

Walter Harden, who lived and guided for bass in Florida during the winter and cooked barbecue in Pennsylvania the rest of the year, was the king of Florida smallmouth bass. Not only did he hold the world record at 14 pounds, but he literally wrote the book on world record bass fishing and designed a couple of lures for Heddon that he endorsed for giant brown bass.

But as Harden was gaining notoriety for his trophy smallmouth fishing, controversy was brewing about the identity of those fish. After all, they looked a lot like largemouth bass.

What is a Smallmouth?

Science does not stand still. That’s as true for ichthyology (the study of fish) as it is for space travel, and the ways scientists defined and described fish in the early 1900s are not the same as how they do it today. Realistically, the way it’s done today will not be the same as how it’ll be done in 10 years … or perhaps next week.

A hundred years ago, science defined the smallmouth by using means such as scale counts along the lateral line or cheek. They initially did not realize that the counts for smallmouths occasionally overlapped with the counts for Florida bass. As a result, a Florida bass—even a 14 pounder—might be identified by a trained and qualified biologist as a smallmouth because it met the recognized standards of the day.

Of course, a lot of serious anglers who were familiar with both Florida bass and smallmouths knew that these were not the same fish. But that sort of “lay knowledge” rarely carries the day in the scientific community … and maybe it shouldn’t.

Controversy

By the 1930s, there was controversy over whether the famed double-digit smallmouths of Florida were actually smallmouth bass or whether they were misidentified largemouths. In fact, there was controversy over whether or not any smallmouth bass lived in Florida waters, despite having been stocked as early as 1908 in North and Central Florida.

Leading the charge against the smallmouth claims were Florida’s top fishing writers, Rube Allyn and Herb Mosher. They challenged anglers to present them with a legitimate smallmouth … and the anglers fell short.

By the 1940s, even biologists were pushing back on their own standards. John F. DeQuine—Florida’s chief fisheries biologist—wrote a story for Florida Wildlife magazine titled “Is the Florida Smallmouth a Fable.” There he said, “I cannot state definitely that there are no Smallmouth bass in Florida, I can only say that neither I nor any other biologist or ichthyologist has seen one.”

Ultimately, it took the work of America’s two greatest bass biologists of the day—Carl Hubbs and Reeve Bailey—to put the matter to rest. In 1949 they published a scientific paper through the University of Michigan Press concluding that the smallmouth bass “has not become established [in Florida] and that the ‘smallmouths’ of reputed record size were largemouth bass….”

How Could That Happen?

Hubbs and Bailey found that “undue reliance” on scale counts was responsible for the misidentifications. Smallmouths have 68 to 81 lateral line scales. Largemouths from peninsular Florida have 65 to 75. The overlap led to confusion. There was similar overlap for scales on the cheek of smallmouths and Florida largemouths. Fisheries scientists needed a better way to define these species. Hubbs and Bailey recommended using the structure of the pyloric caeca (pouches located at the junction of the stomach and intestine), the relative lengths of shortest and longest dorsal spines, pectoral-ray count, and color pattern.

Today, we have sophisticated genetics to “help” us identify fish species … but that’s muddied the waters in new and frustrating ways that we’ll save for another time.

What About Walter?

In the same paper, Hubbs and Bailey recommended that Walter Harden’s 14-pound Florida smallmouth be removed from the record book. Field & Stream magazine (the record authority at the time) agreed.

And so Walter Harden was out, his record was erased, his Heddon lures were taken out of production, his book on how to catch world record bass was a laughingstock, and he went back to cooking barbecue in Pennsylvania. But he kept fishing … and even got into boat sales.

Harden’s Boat Sales—next door to Harden’s Bar-B-Q—advertised “If you can’t make a deal with us, you’re not in the market for a motor.” I bet he had some impressive mounts in the shop. They just weren’t Florida smallmouths.

Harden died in 1957. He’s buried in Green Ridge Memorial Park, Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

Florida Smallmouth Scapegoat

So, who’s to blame for the Florida smallmouth fiasco?

Not Walter Harden or the other anglers who claimed giant smallmouth bass from Florida. They were simply following the definitions of the day’s biologists.

Not publications like Field & Stream. The record Florida “smallmouths” they certified were all checked out and approved by biologists who were following the standards at that time.

If anyone is to blame, it would be biologists of the era. They defined the smallmouth bass in such a way that it overlapped with the Florida largemouth bass. As a result, quite a few Florida largemouths were identified as smallmouths.

And a few of them got into the record books.