Story by Ken Duke

When you think of big bass, quite naturally you start with the world records — 22 pounds, 5 ounces for largemouth and 11 pounds, 15 ounces for the smallmouth. Those are big fish in every sense of the world. They have mass, they have historical import, they stir conversation, and they fuel dreams.

But I’m here to argue that an even “bigger” bass was taken more than 169 years ago … in Ohio of all places … and that it weighed only a fraction of those world record weights.

Allow me to set the stage.

In the spring of 1855, a 19-year-old man from Baltimore was on a train headed west, bound for Cincinnati. He was going to visit his family.

The young man was James Alexander Henshall, and he loved fishing, especially brook trout fishing. Years later he wrote, “Surely there is no lovelier fish than the brook trout.”

Henshall worked as a proofreader in a printing house, saving to continue his education. He planned to become a physician. That’s what put him on the railroad car of the Baltimore and Ohio Railway, headed to Cincinnati.

As the train barreled west, Henshall overheard some talk about fishing. More than 60 years later, he recounted it in his autobiography.

… some gentlemen seated near me were conversing about fishing, and naturally I became an interested listener. Their conversation was mostly about a fish they called black bass, and they were very enthusiastic regarding its gameness and its desirability as a food fish. I had never seen nor read of the fish, nor even heard of it before. The gentlemen were soon joined by the conductor of the train who also proved to be a great admirer of the fish in question…. I resolved to make the acquaintance of the fish at the earliest opportunity, as I was assured by the conductor that it was common in the upper Ohio river, and abundant in all the tributaries.

Henshall started medical school in Cincinnati but reported that “My interest respecting the black bass had not relaxed.” He found a fishing friend who had some bass fishing experience, and they scheduled a trip.

“On the Fourth of July, 1855, we took the train for the little town of Morrow on the Little Miami river, some thirty miles from Cincinnati.”

When they got there, they caught some minnows, and Henshall watched his friend so he could learn the proper technique. Pretty soon, his friend was hooked up.

The bait had scarcely time to sink ere it was seized and the float disappeared from view as the line went racing through the water, cutting erratic angles and curves in a way I had never seen before…. Out leaped a wriggling form of a greenish bronze with wide open mouth, red and cavernous, that seemed to hurl a defiant challenge as with a graceful curve it appeared beneath the surface…. My eyes seemed bulging out of my head as I tried to follow him in his eccentric courses as the line went hissing through the water, now here, now there, with an audible swish as he rushed toward the rocks, then toward a patch of weeds…. Finally he lowered his crest and turned up his armored side to the summer sun in sheer desperation, and as he was being slowly reeled in he seemed to exhibit his defiance and to protest against his undue defeat by slapping his broad tail on the shimmering surface.

Sounds like an epic battle, doesn’t it? It certainly made an impression on Henshall. That smallmouth bass weighed about a pound and a half. Then Henshall’s friend repeated the feat with another bronzeback of about the same size.

That’s when Henshall decided he’d apprenticed long enough. He leapfrogged upstream of his friend and caught his first bass. He described it like this:

I cast toward the flat rock, and when the minnow floated toward the end of its tether I began reeling as rapidly as I could when the bass made a vicious lunge and seized the bait.

Then followed a battle that I will never forget, so vividly was it impressed on my senses. The bass lunged forward toward his rock but I checked him when within a foot of it, whereupon he bounded into the air twice in quick succession, then headed for the flat rock in mid-stream, giving a series of short, savage jerks on the line…. This was a new experience for me. I then discovered that I had a fish to deal with that was capable of no end of original and effective fighting maneuvers that kept me guessing as to what he would do next…. His frantic leaps and violent shaking and whirling of his strong body in mid-air, with wide open mouth and the rotary play of his powerful tail were characteristic, unique and unequalled.

It was Henshall’s first black bass, and it set into motion a career in the sport that in many ways is unequalled in its impact. Though he finished his medical education and became a practicing physician, it’s in the bass fishing world that Henshall made his mark.

He wrote the first book on bass fishing, Book of the Black Bass, in 1881. It contains the greatest line in the history of bass literature: “I consider him, inch for inch and pound for pound, the gamest fish that swims.” Eight years later, he wrote the second book on bass fishing — More About the Black Bass.

Henshall was the first to raise bass in captivity. He designed the seminal rod and reel of his time and is regarded as the father of modern-day bait casting rods. There’s even a good argument to be made that Henshall invented and first popularized the style of casting that we call “pitching.”

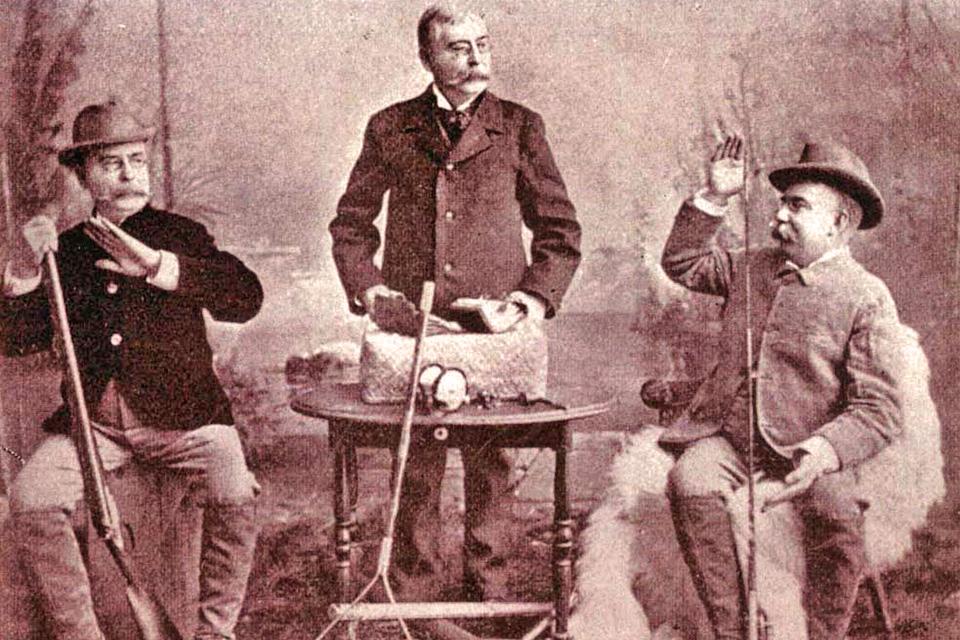

He served as president of the American Fisheries Society in the early 1890s and was a hatchery manager for the U.S. Fish Commission for 20 years. All the while, he wrote the best and most respected magazine stories of the time about the black bass and he caught bass all throughout their range at the time, including a 20 pounder in Florida.

In sum, Henshall was among the earliest and easily the most effective advocates for the black bass and bass fishing. Before Henshall, bass fishing and bass anglers were mostly treated very badly in the press and in the opinions of the angling public. Bass were considered a second-class fish, far below the status of the lordly trout.

Henshall helped to change that and predicted that the bass would one day surpass the trout in the hearts and minds of American anglers.

And it all started with a conversation on a train and with an ordinary smallmouth bass taken from the Little Miami River out of Morrow, Ohio on July 4, 1855.

Bigger have certainly been caught. But maybe none “bigger.”