Story by Ken Duke

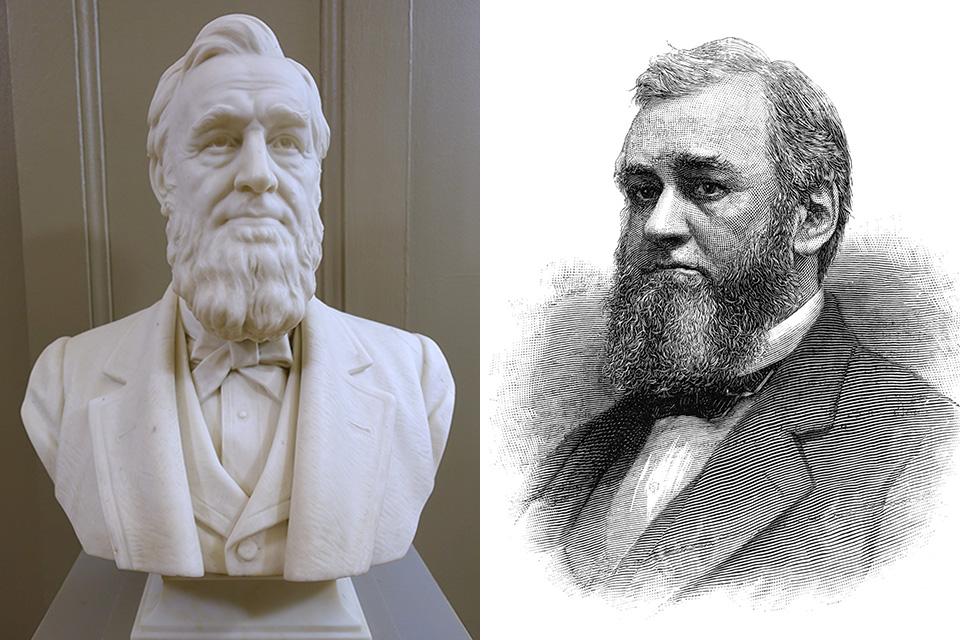

The history of our sport is heavily populated with men and women that most bass anglers have never heard of, yet these people had a profound impact on our sport. If you had to rank those “unknowns,” Spencer Fullerton Baird might be at the very top.

Baird was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1823 and took a great interest in nature as a boy. His family was friendly with the legendary naturalist John James Audubon. Baird attended Dickinson College and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees before he was 18 years old. He was a prodigy as a naturalist.

In 1850, at the age of 27, Baird became the first curator at the Smithsonian Institution in and was personally responsible for creating the museum program there. He pushed for its focus on the natural history of the United States. In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him the first Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries for the U.S. Fish Commission. That’s where Baird made his mark in the bass fishing world, and there’s an excellent chance that you’ve benefited from his efforts.

You see, in the United States at that time, the West was still a frontier. There were no highways or airports, no cars and few railroad tracks. The government was interested in assisting the pioneers brave enough to battle the elements and other challenges they faced. One way they wanted to help was by bringing food fish to the region.

Baird used his position as Commissioner to stock rivers, streams and lakes in the West. To accomplish this noble goal, Baird had Fish Commission staff fill barrels with bass, salmon and other fish and load them onto railroad cars. When the trains would stop to take on water or passengers, the barrels would be emptied into nearby lakes and streams, many of which never held those fish before. Some of the waters were completed unsuited to the fish they were transplanting.

That could never happen today. In fact, there’s a great argument that it shouldn’t have happened in Baird’s time either. What Baird and his staff were doing was nothing less than spreading invasive species. But in the 19th century it was a method of bringing additional food to America’s waterways—particularly in the West.

Even at the time, Baird was criticized for putting fish in places where they might not thrive. He didn’t care. In a letter to an underling who questioned the practice of stocking salmon in waters where they almost certainly could not survive, Baird wrote, “It makes no difference what is done with the salmon eggs. The object is to introduce them into as many states as possible and have credit with Congress accordingly. If they are there, they are there, and we can so swear, and that is the end of it.”

Baird clearly understood politics as well as he understood nature … maybe better. Whether the transplanted fish lived or died was of little import to him as long as he and his department got the credit. After all, who was to say that each and every egg, fry or fingerling had died in a particular stocking effort. Maybe some survived and fed America settlers. That was his assignment.

Though many of Baird’s efforts were a complete failure, bass proved quite resilient and adaptable. In addition to bass, he was able to ship tank-car loads of shad and striped bass all the way across North America to be released in the Pacific, where both species are now well-established.

And he didn’t stop with fish that were readily available in North America. Since carp were popular in Europe, Baird thought they would be well-received in the U.S. After all, they were easy to raise, prolific and a cheap source of protein. Surely Americans would grow to love them.

Well, maybe not … at least not yet. But even though carp have never gained wide popularity here, Baird was so effective at generating interest among Washington’s power elite that nearly every congressman in the entire country jumped at the chance to send free carp fry to constituents. If these “trash” fish seem to be everywhere today, we have Baird and our 19th century congressmen to thank for it.

Baird served the U.S. Fish Commission and the Smithsonian with great distinction for many years. But in November of 1885, his diary shows entries detailing a long list of health issues—heart problems, headaches, leg pain, urinary difficulties. Things got bacd enough that his doctors insisted he stop work altogether and rest for at least a year beginning in May 1887. So, he took his family to the Adirondack Mountains, where his health seemed to improve for a while. But by summer things took a turn for the worse and Baird died in August at the age of 64, likely from heart disease. An auditorium in the Smithsonian is named in his honor.

Say what you will about Baird’s efforts to spread invasive species. The man was following orders of his superiors and using the best science of the time. Few men in American history had a greater appreciation of and positive impact upon nature in this country, and it’s a mistake to judge the past by the standards of the present. It’s better we try to understand than condemn.

Spencer Fullerton Baird is the man principally responsible for the spread of bass into waters west of the Mississippi River—waters they did not occupy before his time as Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries.

And we have absolutely no reason to believe that Baird ever caught a bass.