Story by Ken Duke

A mile high in the Guatemalan section of the Sierra Madres is Lago de Atitlán. It was formed by a volcanic eruption about 80,000 years ago, and it’s the deepest lake in Central America. In places, it’s almost 1,200 feet deep.

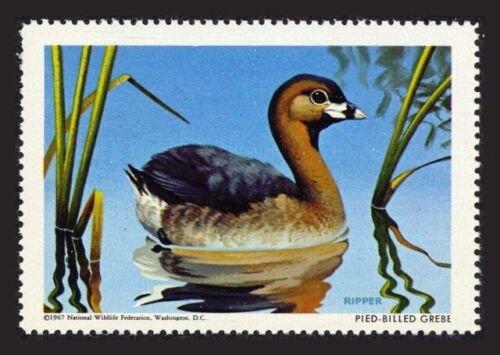

The lake is unique, and as proof of that it was the only place where the giant pied-billed grebe (Podilymbus gigas) could be found. If you’ve never heard of the giant pied-billed grebe, don’t be concerned. Few have, and even fewer have ever seen one. The “poc” as it’s colloquially known is a water bird first identified by naturalists in the 1920s, and although the word “giant” is part of its name, it’s only big when compared to other grebes. An adult measures less than 20 inches long with white plumage in the spring and dark brown feathers the rest of the year. The underside of the bird is dark gray.

The poc’s small wings are incapable of flight but great at propelling them through the water when diving in pursuit of small fish, crabs, snails, aquatic insects, tadpoles, and frogs.

I first heard about the poc about 15 years ago when working on a book (Bass Forever) with the great underwater cinematographer Glenn Lau. We were finalizing a chapter about giant bass, and he told me of a trip he made to Atitlán in the ’60s. Glenn’s visit was only partly about fish. He was equally interested in Anne LaBastille, an attractive blond naturalist who was there studying the grebe.

LaBastille came to Atitlán in the mid ’60s to figure out why the grebe population was in decline. Shortly after she arrived, she was scanning the lake, looking for the birds, when two scuba-diving snorkelers came out of the water. Each had a big largemouth tied to his belt. She estimated the fish to weigh about 15 pounds.

She learned that largemouth and smallmouth bass had been introduced to the lake in 1958 and 1960 by a U.S. airline and a local hotel. They figured that bass fishing would be a nice draw for American tourists. To say that bass thrived there, would be an understatement. They were packing on weight at a rate of two or three pounds per year. Local crabbers and commercial anglers targeting other species reported a precipitous decline in their harvests that began about the time bass were introduced. Most also blamed the new fish for devastating the population of baby pocs—gobbling them up faster than the adults could hatch them.

When LaBastille asked about the largest “lobina negra” (black bass) any of the locals had seen, she was told 25 pounds! The fish had grown from fingerlings to world record size in seven years…or even less, and LaBastille theorized that young grebes were a protein-packed part of their diet.

She told the story of her effort to save the pocs in two books: Assignment: Wildlife (1980) and Mama Poc: An Ecologist’s Account of the Extinction of a Species (1990). One of her most amusing stories concerns a confrontation with the local Minister of Agriculture. In broken Spanish, LaBastille tried to tell him, “The black bass has f***ed up the lake!”

But even though the bass ate grebes, the grebes ate fish. Surely the birds ate bass. Turnabout is fair play, right?

Well, maybe not…or at least not enough to save the grebes. LaBastille observed several adult grebes attempting to feed small bass to their young … to no avail. The baby grebes couldn’t handle the spiny-rayed fish.

Eventually, LaBastille convinced local authorities to amend some fishing regulations and change agriculture practices as measures to save the grebe’s forage base and habitat. They created a sanctuary for the grebes and poisoned the bass inside. There were even Guatemalan postage stamps dedicated to creating awareness and support for the giant pied-billed grebe.

For a while, it seemed that LaBastille and Guatemalan authorities were making real progress toward saving the birds. A 1965 population count reported just 80 grebes. By 1968, there were 125, and by 1973 there were 210. Things were going in the right direction. But in 1976, disaster struck Guatemala in the form of a major earthquake—7.5 on the Richter scale—that killed more than 10,000 people. At Atitlán, the lakebed fractured and much of the water drained out, destroying most of the grebe’s habitat, including the sanctuary. Four years later, only 32 of the birds were left.

Authorities tried relocating some grebes to another lake, including a pair of mating adults. Two eggs were laid. One hatched. For a few days, the parents were seen leading the little chick out onto the lake, but then the chick disappeared. Authorities reported that a largemouth bass had eaten it.

In 1985, just 56 adult pocs were counted. Four years later, there were two.

Ultimately, the giant pied-billed grebe could not withstand loss of habitat, an earthquake, and the largemouth bass. The bird is listed as extinct today.

And the bass of Lago de Atitlán—what happened to them? Well, the bass suffered loss of habitat, too, and commercial fishing has taken a serious toll, but it seems there are still bass in Lago de Atitlán, including some big ones.

Maybe there always will be.