Story by Ken Duke

The black bass is one of the great aquaculture and angling successes in world history. It is Earth’s most widely distributed freshwater fish. There are largemouths in five of the seven continents. They are in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America. No matter where you live, or visit, the odds are that black bass are not far away.

Of course, it wasn’t always like that. At the time of the founding of the United States, the range of the largemouth bass was mostly confined to the eastern half of North America. Subsequent stockings have spread the bass gospel, along with its genetics. And one of the most important and influential places where bass have taken hold is in Japan.

For diehard bass anglers, it’s hard to imagine a world without Japanese bass tackle, without Japanese bass techniques, and without the world record largemouth bass, which came from Japan in 2009. But there was a time — not so very long ago — when there were no bass in Japan.

The Iron Horse

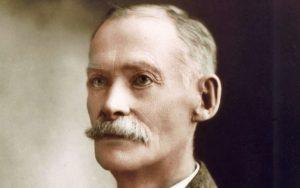

The history surrounding the introduction of largemouth bass to the Land of the Rising Sun is a bit hazy, but it’s generally believed that 75 fingerlings and three adult bass were first stocked in Lake Ashinoko (southwest of Tokyo) in May of 1925 by a wealthy businessman named Tetsuma Akaboshi.

Akaboshi was born in 1882 to a wealthy family. He was the oldest of six sons and seven daughters. His father made a great fortune building military supplies for the Japanese Navy. Being the eldest son, Tetsuma (the name translates to “Iron Horse”) basically inherited everything and lived a very privileged life. He attended boarding school in New Jersey (the Lawrenceville School) and college at the University of Pennsylvania.

But how does a rich Japanese businessman with an Ivy League education decide to import largemouth bass halfway around the world? That’s lost to history, but we can make some reasonable assumptions. We know that Akaboshi was an avid angler (his other hobbies were horseback riding and growing roses). He must have encountered bass while in boarding school or college. There’s a pond on the campus of the boarding school he attended, and Penn is walking distance from the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. Likely he discovered bass there.

What we know for certain is that Akaboshi brought bass to Lake Ashinoko in an effort to restore the ecological balance of the fishery and to help it recover from pollution, overfishing, and dam construction issues. He wrote about it and offered that as his justification.

There are also some Japanese sources that maintain Akaboshi selected largemouth bass for the task “because they are delicious and fun to catch.” Who could possibly argue with that?

So Tetsuma Akaboshi deserves the title of father of Japanese bass fishing.

Gearing Up

Of course, a lot has changed in 100 years. First, largemouth bass in Japan have spread far beyond little Lake Ashinoko (about 1,700 surface acres). Most notably, they are in Lake Biwa, which produced the world record in 2009, weighing 22 pounds, 4.97 ounces.

Second, the Japanese tackle industry has embraced the bass and the American bass market. No other foreign designers and innovators are nearly as important to us, and Japanese fishing products can be found in every serious bass angler’s tackle box and rod locker.

Japan’s initial foray into the American tackle market actually predates the introduction of bass to that country. By the late 19th century, Japanese bamboo fishing poles dominated the American market. A few years later, they claimed most of the silk gut fishing line industry. That dominance continued until nylon monofilament came along, but World War II devastated much of the civilized world as well as the Japanese economy. Japanese tackle manufacturers were among the first to recover because they focused their efforts on the great numbers of American GIs occupying their country. These servicemen had disposable income, and many liked to fish. Japanese manufacturers were happy to equip them.

By the 1950s, the Japanese were focused on the American fishing market, flooding the US with cheap knockoffs of American lures. The quality was woefully lacking, but with retail prices often just 15% of what the name brands were asking, anglers bought the discount options and a lot of American manufacturers suffered as a result.

It wasn’t until the 1970s and ’80s that the Japanese turned things around and began marketing quality products in the US. This resurgence was led by several companies, including Daiwa, Ryobi, and Shimano. Today, it’s hard to imagine walking into a tackle shop and not seeing brands like Gamakatsu, Megabass, Sunline, and too many others to mention.

Enemy Fish

Unfortunately, the status of bass in Japan has changed dramatically since their first stocking in 1925. What were once welcome additions to the aquaculture are now “enemy fish.” Further stocking in Japanese waters is outlawed, and many Japanese citizens support efforts aimed at eradicating the bass wherever possible.

In fact, at the government-run museum and restaurant for Lake Biwa, bass are on the menu, and anglers are required to keep and kill any bass they catch from most Japanese waters—though some of the slippery things get away. “Oops!” Only certain guides and fishing industry professionals have authorization to release bass back into the water alive.

Today, we’re more aware and sensitive to the concept of invasive species. Bringing a non-native or “alien” species into a new ecosystem can have unintended and undesirable effects. Had we been aware of such threats a century ago, it’s unlikely that there would be any bass in Japan today … or in a lot of other places.

While some might argue that the bass has been a mixed blessing to Japan, no one could reasonably say the reverse. Whether we’re talking tackle, techniques or the world record largemouth, Japan has been great for our sport, and the history of bass and bass fishing cannot be told without also telling of its Japanese influence.